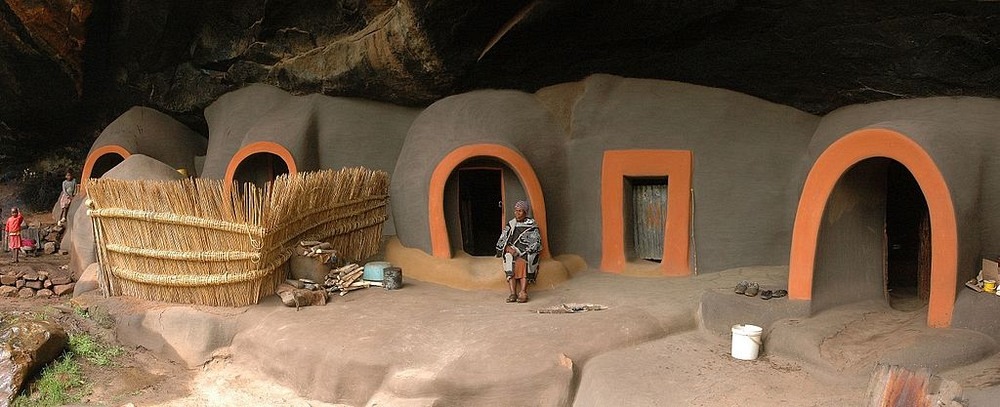

These smooth walled, well maintained, igloo-shaped mud houses near the village of Mateka, in Lesotho, belie their age. Although they appear very recently built, these houses are nearly two hundred years old and have been continuously inhabited, generation after generation, by the descendants of the original people who built them in the early 19th century.

The Ha Kome Cave Village lies a bit off the beaten track, which is true for pretty much any place in the landlocked country of Lesotho that is completely surrounded by South Africa.

What is now Lesotho was originally inhabited by the Sotho–Tswana people when the Zulus started attacking villages and encroaching on their land, forcing the Sothos to flee up into the mountains. Here, continuous attacks from the Zulus forced local tribes to join together for protection, and by 1824, King Moeshoeshoe had established himself as king. This difficult time of widespread chaos and warfare is known as Difaqane or Mfecane, and is one of the darkest periods in the history of Lesotho. It was during Difaqane the ghastly practice of cannibalism arose.

The plundering raids, compounded by drought brought famine so severe that groups of people in several parts of Lesotho began to eat each other. What originally started out of hunger eventually became a habit as the cannibals took a liking for human flesh. Cannibals were said to form themselves into hunting parties and set off daily in search of victims. D.F. Ellenberger, a missionary who arrived in Lesotho in the 1860s, estimated that there were about 4,000 active cannibals in Lesotho between 1822 and 1828, who each ate, on an average, one person a month. Extrapolating these figures, one arrives at a staggering figure of 288,000 people who fell victim to cannibalism. Overall, between one to two million people lost their lives due to warfare during a ten year period.

To escape the gruesome slaughtering and cannibalism, a handful of tribesmen fled to what is now the Ha Kome Cave Village, and built the mud houses inside the cave. The mud houses lie under a huge overhanging rock with the rock wall serving as the back of the houses.

King Moeshoeshoe himself was personally affected by cannibalism—his own grandfather was abducted and devoured when they were passing through a cannibal-infested area. When the King learned about the tragedy, instead of wreaking revenge, he decided to make peace with the cannibals. The story goes that Moshoeshoe instructed his warriors to capture the cannibals but not harm them. The captured cannibals were then given a sumptuous feast at the end of which Moshoeshoe offered each one a cow and a plot of land on which to build a house, saying, “You are the graves of my ancestors, you belong among us.”

King Moeshoeshoe

Moshoeshoe was an astute, benevolent leader whose tact was way ahead of his time. It has been suggested that Moshoshoe’s diplomacy may have influenced modern South African leaders, and the example of Moshoeshoe forgiving the cannibals who ate his grandfather is compared to Nelson Mandela’ act of reconciliation in taking tea with Betsy Verwoerd, the wife of South African Prime Minister and the “the architect of apartheid” Hendrik Verwoerd.

Cannibalism died out by the late 1830s, but these stories survived both in oral tradition and songs, as well as in literary works and history texts. The stories are complemented by the existence of cave houses such as the Ha Kome Cave Village and other sites associated with cannibalism in the landscape.

No comments:

Post a Comment