MOST OF THE Americans arrived in Port-au-Prince from the U.S. by private jet early on the morning of February 16. They’d packed the eight-passenger charter plane with a stockpile of semiautomatic rifles, handguns, Kevlar bulletproof vests, and knives. Most had been paid already: $10,000 each up front, with another $20,000 promised to each man after they finished the job.

A trio of politically connected Haitians greeted the Americans when their plane landed around 5 a.m. An aide to embattled Haitian President Jovenel Moïse and two other regime-friendly Haitians whisked them through the country’s biggest airport, avoiding customs and immigration agents, who had not yet reported for work.

The American team included two former Navy SEALs, a former Blackwater-trained contractor, and two Serbian mercenaries who lived in the U.S. Their leader, a 52-year-old former Marine C-130 pilot named Kent Kroeker, had told his men that this secret operation had been requested and approved by Moïse himself. The Haitian president’s emissaries had told Kroeker that the mission would involve escorting the presidential aide, Fritz Jean-Louis, to the Haitian central bank, where he’d electronically transfer $80 million from a government oil fund to a second account controlled solely by the president. In the process, the Haitians told the Americans, they’d be preserving democracy in Haiti.

It was too good a deal for the band of semi-employed military veterans and security contractors to turn down.

But a day after the Americans landed in Haiti, they would find themselves in jail and at the center of a political uproar, with Haitians asking what a group of foreign mercenaries was doing at the central bank and who they were working for. Within three days, Kroeker and his team would be released and sent back to the U.S., having somehow managed to escape criminal charges in Haiti.

Many details of the operation remain murky, but based on interviews with Haitian law enforcement and government officials, as well as a person with direct knowledge of the plan, a picture of the clumsy effort emerges. What at first resembled a comedic plot about a group of ex-soldiers looking for a quick and easy mercenary score was in fact a poorly executed but serious effort by Moïse to consolidate his political power with American muscle.

Neither Moïse nor the Haitian Embassy in Washington, D.C., responded to requests for comment.

None of the Americans spoke directly with Moïse or received official paperwork from the Haitian government authorizing them to undertake the mission, according to the person with direct knowledge of the operation. Yet Jean-Louis and the plot’s other key organizer, Josué Leconte, a Haitian-American from Brooklyn and close friend of Moïse, do not appear to have been rogue operators.

The Americans arrived at a tumultuous political and economic moment in a country with a history of unrest. Since last July, when Moïse tried to raise fuel prices by as much as 50 percent, intermittent protests have paralyzed Haiti.

From 2008 to 2017, Venezuela provided Haiti with about $4.3 billion in cheap oil under the Petrocaribe Accord, which Venezuela signed with Haitiand 16 other Caribbean and Central American countries. Haiti had a particularly favorable deal: Forty percent of the money owed to Venezuela was repayable over 25 years at an annual interest rate of 1 percent. In the meantime, Haiti was free to pump its revenue from that oil into the Petrocaribe fund. The fund was supposed to support hospitals, clinics, schools, roads, and other social projects, and helped prop up the Haitian government after the devastating 2010 earthquake and Hurricane Matthew in 2016.

But Trump administration sanctions on Venezuela and financial mismanagement by the Haitian government led the Haitian central bank to halt payments to Venezuela, and the Petrocaribe agreement effectively ended in early 2018. A Haitian Senate investigation found that the fund’s nearly $2 billion had been largely misappropriated, embezzled, and stolen, primarily under Haitian President Michel Martelly’s leadership between 2011 and 2016.

Moïse came to power in 2017, after the Port-au-Prince district attorney accused him of money laundering. The corruption allegations, combined with the end of cheap Venezuelan oil and credit, created a perfect storm of popular outrage. In recent months, Moïse and Haitian Prime Minister Jean-Henry Céant have been vying for power, and Moïse’s decision to back the Trump administration’s recent efforts to undermine Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro set off a new round of popular street protests in Haiti, with protesters calling for Moïse to step down. Under the Haitian constitution, that would have made Céant the country’s leader.

The Americans were told that the Petrocaribe fund is controlled by Moïse, Céant, and the central bank’s president, Jean Baden Dubois. Because of the widening political rift between the president and the prime minister, that arrangement left the $80 million effectively frozen, according to the person with direct knowledge of the operation.

Leconte and Jean-Louis told the Americans that by moving the money into an account Céant and Dubois could not access, Moïse could more effectively lead the country, hence the promise that they would be supporting Haiti’s democracy. The fund was the government’s only significant economic instrument, and the move would secure Moïse’s position and freeze out his prime minister. It is unclear what Moïse intended to do with the money once he gained control of it.

Leconte paid the Americans for the operation, according to the source with direct knowledge. Leconte and his business partner, Gesner Champagne, who also met the Americans at the airport in Port-au-Prince, were acting as cutouts, giving Moïse plausible deniability, the Americans were told.

In return for helping Moïse, the president promised Leconte and Champagne that he would give a nationwide telecom contract to Preble-Rish Haiti, the engineering and construction company Leconte and Champagne run together, Jean-Louis and Leconte told the Americans.

JEAN-LOUIS, KROEKER, and his five teammates arrived at the Banque de la République d’Haïti in downtown Port-au-Prince around 2 p.m. on Sunday, February 17, roughly 36 hours after the Americans had landed. In addition to being a presidential aide, Jean-Louis was the former director of the national lottery, which is run out of the central bank. It is unclear if his previous job was related to his having been selected to transfer the money.

The Americans pulled up in three cars and got out. They were heavily armed and stood protectively around Jean-Louis. The bank was closed, but Jean-Louis told a security guard at the door that they were there on bank business, according to the source with direct knowledge. Suspicious of their intent, the security guard refused to let them in. Instead, someone alerted the police.

A two-hour standoff ensued on Rue des Miracles. Penned in by the police, Kroeker called a seventh member of his team to help negotiate their release. Dustin Porte, an electrical services contractor and former member of the Louisiana National Guard who spoke French, showed up and spoke to the police on his team members’ behalf. The contractors eventually surrendered, telling the police that it was all a big misunderstanding — and that they were there on a government mission, according to the Miami Herald.

The police asked the Americans why, if their mission was legitimate, they hadn’t gone through official channels, a senior Haitian law enforcement source told The Intercept.

“Because the president doesn’t trust you guys,” one of the contractors replied, according to the Haitian law enforcement official, who asked not to be named because he was not authorized to speak publicly about what happened.

Haitian police arrested Kroeker, the team leader; former Navy SEALs Christopher McKinley, 49, and Christopher Osman, 44; former Blackwater contractor Talon Burton, 51; and Porte, 43. They also detained the two Serbians, Danilo Bajagic, 36, and Vlade Jankovic, 40. Photos of their weapons and tactical gear, which included six semiautomatic assault rifles, six handguns, knives, and at least three satellite phones, soon surfaced on social media.

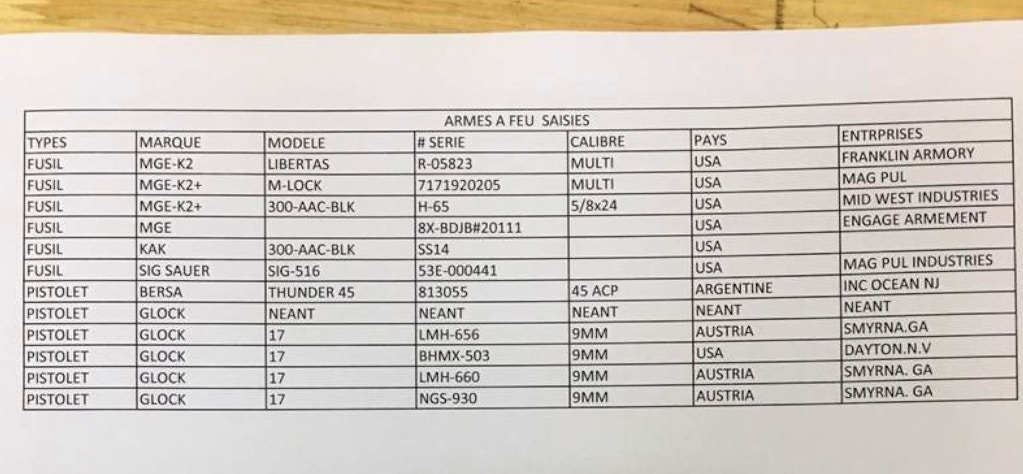

Haitian police sources say that some if not all of the mercenaries brought their arms with them and that the makes, models, and serial numbers of the weapons have been provided to the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. U.S. authorities have so far failed to bring charges against the contractors for illegally traveling out of the United States with their weapons, which requires a license.

Jean-Louis had apparently managed to flee during the lengthy standoff. But after the Americans were booked into the jail, Michel-Ange Gédéon, the director general of Haiti’s National Police, fielded calls from Jean-Louis, senior presidential aide Ardouin Zéphirin, and Haitian Justice Minister Jean Roudy Aly, who claimed variously that the Americans were conducting “state business” and there doing “work for the bank,” according to a well-placed police source. In each case, the callers conveyed that Moïse had authorized the Americans and that they should be released. Gédéon refused.

A list, created by Haitian police and acquired by Haïti Liberté, of the serial numbers of weapons the mercenaries had.

A list, created by Haitian police and acquired by Haïti Liberté, of the serial numbers of weapons the mercenaries had.

Céant did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Shortly after the Americans were arrested, he took to the airwaves to call the team “terrorists” and “mercenaries” who had been trying to get to the bank’s roof so they could assassinate him and unspecified parliamentarians. He later walked back the statements, saying that they were a “hypothesis.”

On Monday, Haiti’s parliament voted to oust Céant as prime minister, but Céant has remained defiant. “There are MPs who have decided to do something illegal and unconstitutional and that goes against principles, republican traditions, and parliamentary traditions,” he told the Haitian daily newspaper Le Nouvelliste. “I am still in office as prime minister.”

THE CAPER MIGHT have been successful had any of the American participants had previous experience conducting a clandestine mercenary mission in a sovereign country. Instead, they were a mixed bag of mostly military veterans, including one former SEAL who had recently been charged with assault for a road rage incident in southern California and another who was a body builder with a sideline as a country music singer. There was Kroeker, who among other ventures ran a truck suspension business; Burton, a former Army military police officer and State Department security contractor; and Porte, the owner of a small electrical contractor that won a one-time $16,000 contract with the Department of Homeland Security.

Kroeker, according to a person with direct knowledge, had assured his colleagues that the mission would be easy. But while the Americans were well-armed, they lacked other basic provisions of a secret security operation for hire: insurance coverage, a medical evacuation plan, legal authority to bring their weapons into Haiti, or an escape plan if things went bad.

“They had no idea what they were doing,” said the person with direct knowledge, who requested anonymity to speak publicly about the clandestine mission.

After the State Department secured the Americans’ release, everyone involved in the operation scattered. By the time the Americans were freed, Jean-Louis and Leconte had fled Haiti. Leconte flew back to the U.S. from the Dominican Republic, according to the person with knowledge of the operation; a day after he landed in New York, his Facebook profile was taken down. On February 24, Leconte ran away from a reporter who asked for comment outside his Brooklyn home and hid in a parking garage.

Chris Osman, one of the ex-Navy SEALs and the only member of the team to publicly discuss the Haiti operation so far, wrote on Instagram that he was in Haiti doing security work for “people who are directly connected to the current president.” Osman hinted at the Haitian political intrigue behind the scheme, posting that he and his colleagues “were being used as pawns in a public fight between [Moïse] and the current Prime Minister of Haiti.” Osman has since deleted his post.

Leconte and Champagne had discussed a possible follow-up contract with Kroeker if the money transfer was successful, according to the person with direct knowledge of the mission. It is unclear what that assignment might have been.

No comments:

Post a Comment