Today marks the beginning of Black History Month. It's the annual time of year when we as a nation collectively reflect upon and pay tribute to the accomplishments of generations of brilliant African Americans who, despite centuries of marginalization, were able to challenge and rise above the bigotry-based atrocities they regularly faced. Determined to seek genuine equality, 20th-century civil rights activists like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Jesse Jackson, Fannie Lou Hammer, John Lewis, Thurgood Marshall, Rosa Parks, and many others confronted the societal ill that is racism in peaceful protest, speaking truth to power while fueled by courage, resiliency—and good food.

"I was a college student at Fisk on April 4, 1968, the day MLK was killed," my aunt recently shared with me over brunch. "The only place my friends and I went for food was a good ole hole in the wall, Ma & Pa Strickland's. You ordered food to your table—basic soul food; mac 'n' cheese, greens, fried chicken, pork chops, and fried whiting on white bread with hot sauce was popular."

Horrified and heartbroken, these historically black college & university (HBCU) students found themselves gravitating toward this local eatery in an effort to process their grief. Perhaps this is because, in many ways for the Black community, food equals love: It can create a sense of comfort and security in an ever-changing and turbulent world. Also, it symbolizes the tenacity of Black culture and history, with dishes that have continued to stand the test of time since the days of slavery in the U.S. Above all else, it has the power to bring people together, nurturing existing connections while fostering new ones. There's a reason why this cuisine is referred to as "soul food"—under the right set of circumstances, it can literally nourish your soul.

Food's ability to symbolize cultural identity, community, and comfort is, of course, not unique to Black Americans. However, there is something to be said about the foods that nourished the bodies and souls of those civil rights leaders who selflessly risked their lives to hold others accountable for that which was promised to all Americans in the Declaration of Independence ("life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness"). Though many of these dishes may not represent the pinnacle of healthy eating as we view it today, these meals were substantial enough to provide these activists with the energy to persevere in their pursuit of social justice and peace, in spite of the many volatile adversities they were unjustly subjected to. So with that in mind, here are five foods that helped to fuel the civil rights movement.

Coffee

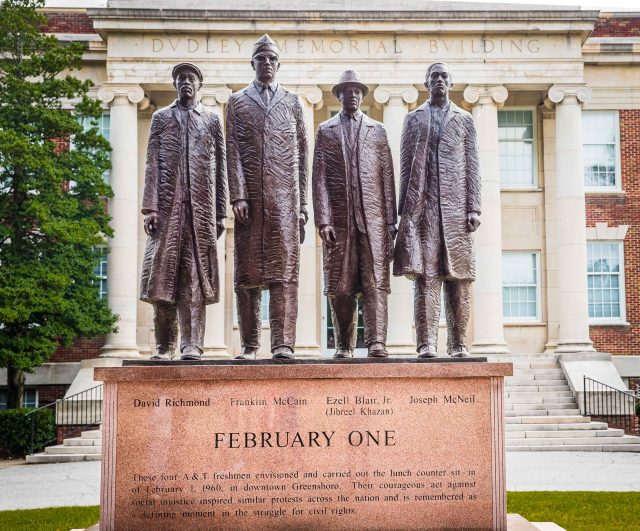

On February 1, 1960, when four Black college freshmen from North Carolina A&T University, Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Joseph McNeil, sat down at the lunch counter of F.W. Woolworth Company in Greensboro, NC, each attempted to order a cup of coffee. Because this was a "whites-only" establishment, they knew rejection was inevitable. But rather than seek sustenance elsewhere, the Greensboro Four, as they are known by today, stood their ground, refusing to leave even as restaurant patrons—both Black and white—reportedly urged the young men to go.

Inspired by the nonviolent protests of Gandhi and the Freedom Riders protesting segregated busing systems, these young men were determined to use peaceful tactics to demonstrate to the public how the dehumanizing inequities dictating the social norms of this era could no longer hold any power over the Black community. Despite various threats and harsh criticisms, they remained in their seats until the store closed, and the act of ordering a cup of coffee ultimately ignited the powder keg for the sit-in movement across southern college campuses.

Baked goods

During the 1950s, a woman in Montgomery, AL, named Georgia Gilmore, who was fired from her position as a cafeteria worker after speaking out against the discriminatory actions of a white bus driver, was able to transform this misfortune into purposeful action. After participating in community meetings at the Holt Street Baptist Church, Gilmore "decided she would use her culinary talents to feed and fund the resistance, which came to be known as the Montgomery bus boycott," the New York Times reports.

At the encouragement of Martin Luther King, Jr., Gilmore pioneered an underground organization of women known as Club From Nowhere, who would sell pies, cookies, pound cakes, and biscuits out of their homes, at protest meetings, on street corners, and in local small businesses to help finance the Montgomery bus boycott.

According to NPR, "[Gilmore's] back-door restaurant became so popular that people waited in line to be fed. The crowds served as cover for King and other movement leaders, who held clandestine meetings there."

Gumbo

As restaurant owner and chef Leah Chase once said in an interview with NOLA.com, "Food builds big bridges. If you can eat with someone, you can learn from them, and when you learn from someone, you can make big changes."

It is this mentality that inspired Chase and her husband Edgar "Dooky" Chase to open the doors of their New Orleans-based restaurant Dooky Chase to civil rights activists of all creeds and races during the 1960s, spitting directly back into the face of the state and city ordinances deeming most interracial gatherings as illegal. This legendary restaurant was considered a go-to safe haven for activists like Martin Luther King, Jr., John Lewis, Freedom Riders, Thurgood Marshall, Jerome Smith, Rudy Lombard, Oretha Castle Haley, and other local protestors when they would meet to discuss civil and economic rights issues. The upstairs meeting room was also where many would secretly conduct strategy meetings for protests. And as these individuals collectively organized next steps for bus boycotts, sit-ins, and strikes, they were treated to bowls of Leah Chase's famous gumbo and other Creole fare.

"We changed the course of America in this restaurant over bowls of gumbo," Chase continued. "We can talk to each other and relate to each other when we eat together."

While there are many ways to make gumbo, Chase's recipe crown jewel is gumbo z'herbes or green gumbo. Unlike other styles of gumbo which typically use a heavy brown roux and can be very meat and seafood forward, the majority of ingredients used in this dish are leafy greens, like mustard greens, collard greens, turnip greens, beet tops, cabbage, romaine lettuce, watercress, and spinach.

Fried chicken

Fried chicken was another popular dish of choice among civil rights activists served at Dooky Chase and Club From Nowhere.

Another popular eatery civil rights leaders frequented was the Atlanta-based restaurant Paschal's. As one of the only white-tablecloth restaurants in the Deep South that would seat Black Americans, Paschal's is regarded as the unofficial headquarters of the civil rights movement, and its signature fried chicken recipe is still regarded as one of the South's best-kept secrets.

"Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Andrew Young, Hosea Williams, Ralph David Abernathy, and Joseph Lowery would strategize over Paschal's abundant plates of Southern cooking: fried chicken, catfish, fried green tomatoes, collards, and mac 'n' cheese. Co-owners and brothers Robert and James Paschal would provide free food and meeting space," according to NPR.

Plant-based foods

Traditional soul food dishes weren't the only foods embraced by activists in the civil rights movement. In fact, comedian and activist Dick Gregory was not only a proud vegan, but also he frequently spoke about how he viewed this diet as a proactive exercise in social justice, even writing a book that outlined ways people can incorporate more natural, nutritionally dense foods into their diet through a lens of Black consciousness called Dick Gregory's Natural Diet for Folks Who Eat: Cookin' With Mother Nature. Though Gregory wasn't always a practicing vegan, he reportedly changed his eating habits by first transitioning to a vegetarian diet in 1965, eventually eliminating all animal-based products from his diet over the next few years.

Gregory attributed this lifestyle pivot to working alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose approach to activism was based on appealing to others' humanity via nonviolent means.

"I had been a participant in all of the 'major' and most of the 'minor' civil rights demonstrations of the early sixties. Under the leadership of Dr. King, I became convinced that nonviolence meant opposition to killing in any form," Gregory penned in his memoir Callus on My Soul. "I felt the commandment 'Thou Shalt Not Kill' applied to human beings not only in their dealings with each other—war, lynching, assassination, murder, and the like—but in their practice of killing animals for food and sport. Animals and humans suffer and die alike. Violence causes the same pain, the same spilling of blood, the same stench of death, the same arrogant, cruel, and brutal taking of life."

No comments:

Post a Comment